— Excerpt from The Urban Food Forester: Creating a Low Maintenance Food Garden Inspired by Nature by Justin Calverley

The Urban Food Forester

Growing your own fruit, veggies and herbs can be time-consuming if you use a traditional approach of planting annuals every year. But there is another way. By harnessing the power of perennials, trees and shrubs, you can establish a thriving ecosystem that requires minimal upkeep – perfect for busy people.

Justin Calverley, author of the bestselling The Urban Farmer, reveals the secrets of our woodlands and how their low-maintenance model can revolutionise our outdoor spaces. Known as ‘food forests‘, these self-sustaining backyard ecosystems focus on long-living perennial plantings. A food forest garden, once established, will continue to give back year after year, reducing maintenance and increasing biodiversity.

Whether you’re a seasoned gardener or just starting out, you’ll learn the practical steps to creating a garden that will provide lasting benefits for you, your family and the environment.

–

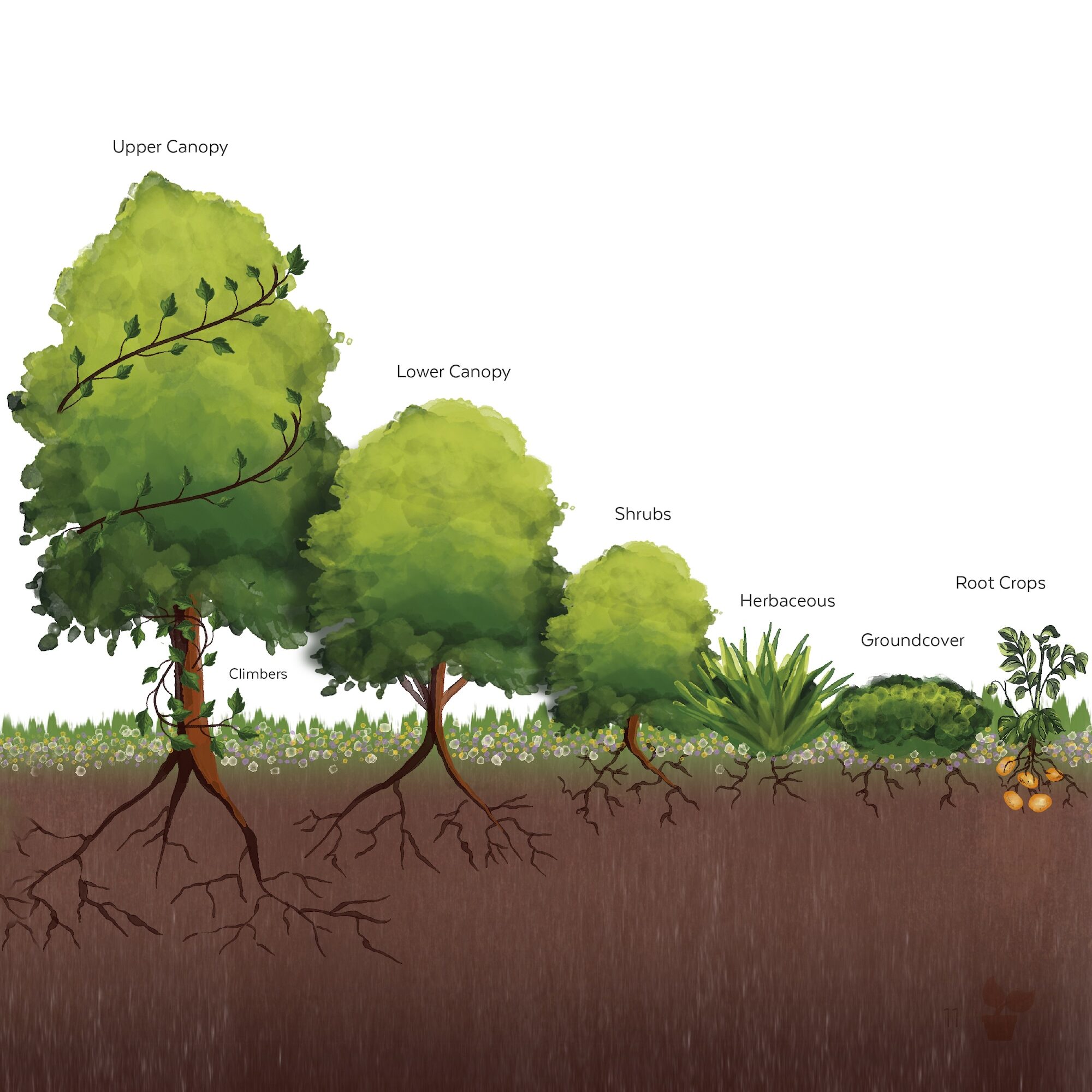

Layers of a food forest

Upper canopy

The upper canopy layer is incredibly important to a food forest because it sets the tone regarding the volume of light that can pass through. The canopy height is usually more than 10m. Regarding yields, you can use this layer for harvests of nuts and fruits, but the height of these trees can make this difficult. Other yields can be of great use, such as wood for building and fuel. Periodically removing some limbs for these purposes will let more light penetrate to the forest floor, which will help vary the diversity and performance of the lower-tiered species.

You can also obtain yields from the canopy layer below ground level. The roots of larger trees can assist in stabilising slopes to minimise erosion. Their powerful roots can also break through dense rocky soil types. Leguminous species, such as acacias, are great for establishing food forests because their root nodules contain bacteria that convert nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into a solid form that they can use. Nitrogen is arguably the most important nutrient for plants because they use it to form new tissue. Plant stems and leaves depend on nitrogen being available. If you have a legume as the main upper canopy species, your food forest can supply itself with a vital fertiliser, which is a huge tick when thinking about its sustainability.

Lower canopy

Commonly, the lower tree layer is the food forest’s highest producer of fruit. Our beloved pomes (such as apples), stone fruits and citrus are the first choices when it comes to filling this layer, but there are plenty more options. These species commonly occupy the 4–9-metre-high layer in a food forest. In smaller urban scenarios, where large canopy trees aren’t an option due to their root strength and potentially lethal outcomes if a limb or entire tree was to fall, the lower tree layer can double as a canopy layer.

Shrubs

A shrub is a multi-trunked species that commonly occupies the 1–3-metre height zone of a food forest. This group of plants provides harvests of leaves, fruits and nuts – think tea leaves, blueberries and currants. This layer provides the most diversity in yields for the urban food forester. The main reason for this is their size. Maintaining and harvesting without having to leave the ground is attractive to most gardeners.

Herbaceous

Herbaceous plants can be annual or perennial, but their key feature is that they don’t produce lignin, or woody material. As plants grow higher to better access light, they accumulate lignin as a strategy to become more rigid and support their increasing weight. Not all perennials have this strategy – herbaceous plants can be ground-hugging, which makes some of them interchangeable with actual ‘groundcovers’, but other species can grow 3m tall. This layer of plants can yield common edibles as well as remedies, dyes and fibres.

Groundcovers

Being the lowest-growing layer, up to 1m tall, groundcovers have adapted to be shade tolerant. The numerous plant layers above them only allow shards of light through at various times of the day for these plants to survive on, and they have excelled at this survival if you ask me. Many common urban garden ‘weeds’ are categorised as groundcovers. Possible harvests include fruits and leaves, but that’s not their only yield. A constant and consistent groundcover layer of vegetation protects the upper layer of soil from moisture loss due to evaporation. When this layer stays moist, seeds can germinate readily and the protective process continues.

Climbers

These plants have adapted to fill gaps in all layers so they can take advantage of any available light. Because they require structural support to climb, they are usually incorporated once the upper canopies have had time to mature. Yields from these plants are commonly fruits such as grapes or passionfruit. Their long stems can also be harvested as fibres and other creative construction materials.

Root crops

Below ground level, plant roots can be shallow, moderate or deep. Roots not only stabilise a plant in the ground but also store nutrients and energy (most commonly in the form of carbohydrates). Roots also maintain symbiotic relationships with beneficial bacteria and fungi. Keeping this in mind, many species of edible fungi can be harvested as a result of a healthy root layer.

—

Note: please take extreme caution when harvesting mushrooms because an incorrect identification can result in devastating outcomes.

The Urban Food Forester: Creating a Low Maintenance Food Garden Inspired by Nature by Justin Calverley

Published by HarperCollins

Buy Now