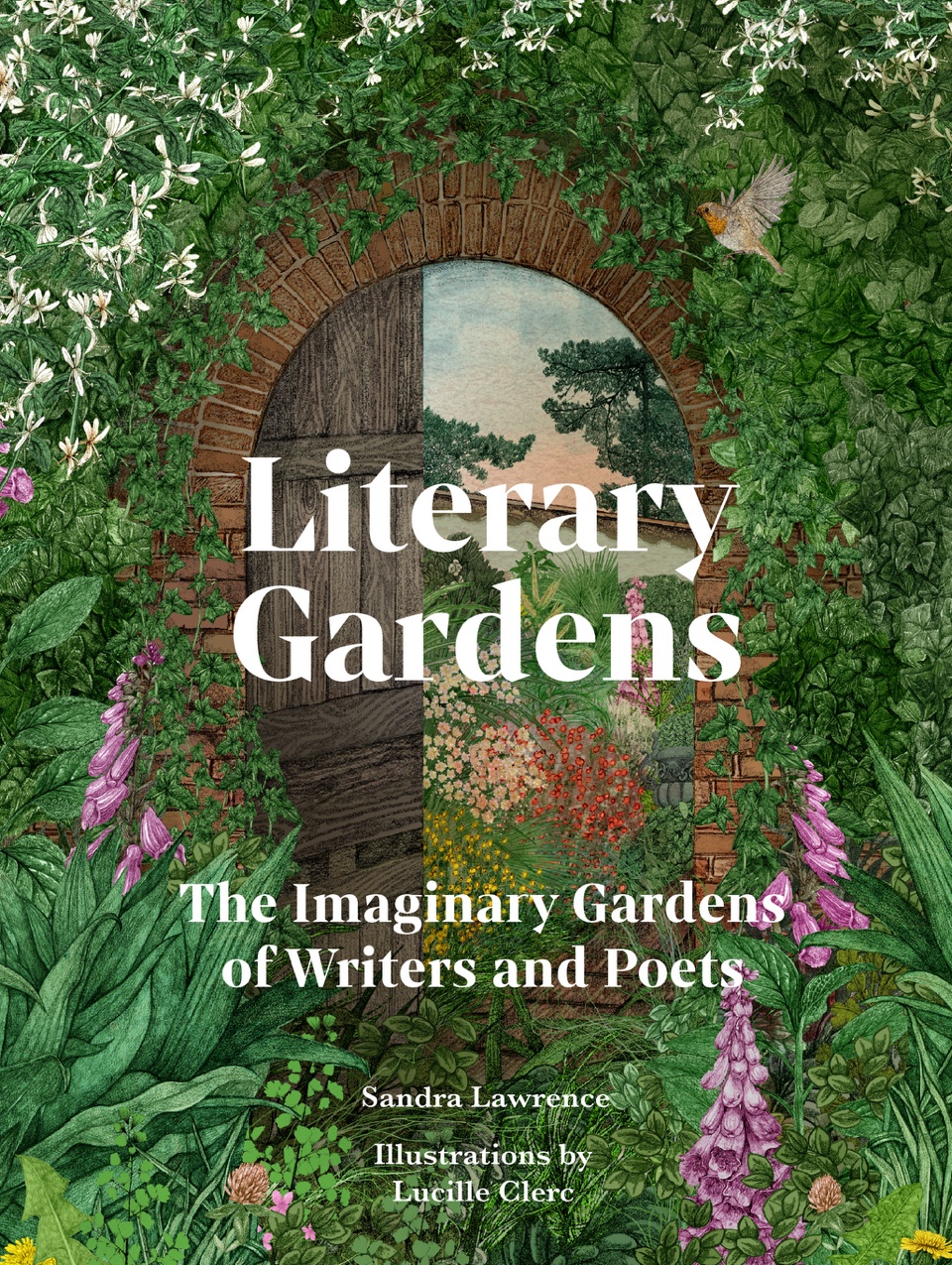

— Excerpt from Literary Gardens by Sarah Lawrence

In the book Literary Gardens, author Sandra Lawrence leads readers through fifty of the most magical gardens ever imagined in literature. Each chapter reveals how writers use gardens not just as settings, but as symbols of paradise and desire, romance and debauchery, adventure and escape.

Among these storied landscapes is one of the most deceptively innocent of all: Mr McGregor’s garden. In Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit, the most perilous place in the world isn’t a dark forest but a tidy English vegetable patch. Within this small square of cabbages, radishes and lettuces, innocence meets danger, order collides with instinct, and the neat geometry of human cultivation becomes a trap for one small, hungry rabbit.

This excerpt from Literary Gardens invites us to rediscover the tension between the wild and the domestic – to see how even the humblest patch of earth can bloom into a world of story, imagination and perilous delight.

Illustration of Mr McGregor’s garden by Lucille Clerc

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

— Beatrix Potter, 1902

‘First he ate some lettuces and some French beans; and then he ate some radishes’

Once upon a time there were four little rabbits… It is perhaps fitting that one of the world’s most famous nursery stories should have a fairytale opening. The Tale of Peter Rabbit starts in the woods, the natural world, where four little bunnies live with their mother under a fir tree. In most fairytales, venturing into the forest is the moment where the hero leaves behind any sense of security, to face the dangerous, the unknown. Here, it is the other way around. The scariest place on Earth is a humble vegetable patch, ordered, neat – and lethal.

The first time we see the rabbit family they look like animals children might glimpse in real life: sweet, furry – and naked. Their burrow is warm and safe, but they cannot not stay there. Mother must find food. She tells them to be good and to stay close to home. Fixing her son’s little blue jacket collar, she is adamant: do not go anywhere near Mr McGregor’s garden. Mother rabbit cannot mince her words, for the sake of her brood. They are a one-parent family because Mr McGregor put their father in a pie. While the good little bunnies pick blackberries in the wood, however, naughty Peter has other ideas.

Gates are always liminal spaces in folklore, and the one Peter squeezes under – a homely wicket-affair, edged with holly, a plant of both woodland and the cultivated garden – would be passed through the other way by any other hero, leaving civilization to face the wild wood. Peter is not any other hero. This adventurer is of the wild wood himself, and he is about to face his nemesis – an elderly man.

Readers familiar with Beatrix Potter’s charming cottage in the English Lake District might be forgiven for assuming that Mr McGregor’s garden was based on the author’s own. In reality, Potter did not purchase Hill Top until 1905, three years after Peter Rabbit was published. Much like her turning the traditional hero story on its head by sending a wild creature into the human world, it is far more likely that Potter’s kitchen garden is based on the one she invented for her villain.

Potter was born and raised in London. South Kensington was home to the Natural History Museum, and the young Beatrix was passionate about all things natural. Her intricate botanical illustrations, especially of fungi, are well-respected today but as a Victorian woman she was not taken seriously. Her paper on fungi, submitted to the Linnean Society in 1897, was unsuccessful (female Fellows were fiercely opposed until 1904) so she turned to a much more ‘ladylike’ outlet for women artists: children’s books. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was privately printed in 1901 and commercially published in 1902 by Frederick Warne & Co.

Potter may not have entirely invented Mr McGregor’s vegetable patch. It is widely suggested she based The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies on her uncle and aunt’s walled garden at Gwaenynog in Wales, and Mr McGregor’s neat rows of cabbages and beans are typical of nineteenth-century kitchen gardens up and down the land. Potter’s detailed illustrations prove she was familiar with her subject. From the old-fashioned, long variety of radishes Peter consumes when he first arrives in the garden, through rows of French beans and lettuces to the detailed representations of pelargoniums that Peter later knocks over in his haste, it is clear this world has been drawn by someone with a background in botanical illustration.

Potter’s familiarity with the process of gardening is also clear. The spade speared into the earth as Peter gobbles his ill-gotten gains reminds us of the human threat. Even the robin cannot save him as, searching for parsley, a traditional herbal remedy for tummy ache, he ventures ever closer to the non-natural: the pots of cane-supported vegetables, the cold frame and, finally, Mr McGregor himself. We first see him on his hands and knees, planting out seedlings in rows, looking like anything but an enemy. He chases Peter with human weapons, a rake, then a sieve, but the most horrific image in the book is not from a deliberate attack.

The image of a rabbit caught in netting is perhaps even more poignant today than it would have been in Potter’s time, in that modern, plastic netting is deadly. Happily, Peter’s trap is made from twine and his friends the sparrows can release him, but the garden remains an obstacle course. Peter’s next hiding place, a watering can, is full. Inside the shed, a place many children would have been familiar with, upturned terracotta pots, a broom, spade and trowel all become potential instruments of torture. Even an ornamental goldfish pond is set with a trap of the feline variety.

As Peter creeps away we glimpse more of Mr McGregor’s immaculate potager, complete with low box hedges and regimented cabbages. From a wheelbarrow we gaze with Peter as he yearns for the safety of the forest, only kept at bay by high yew hedges. It is so close, but there is one more barrier to freedom: the old gardener himself, currently hoeing onions.

Potter’s skill lies with the Brechtian concept of making the familiar strange, that an audience may view something ‘normal’ more dispassionately. Her readers would have known kitchen gardens as comforting havens, yet through Peter Rabbit, she shows us that not everyone sees things the same way we do. As Peter scoots through the (cultivated) blackcurrant bushes to the safety of the (wild) blackberry patch, Mr McGregor is already making his clothes into a scarecrow. Little bunnies have no place in the human world, especially not wearing jackets and shoes.

While the ‘good children’ get milk and blackberries, Mother Rabbit gives Peter a dose of chamomile tea, presented like a classic Victorian nursery punishment. We do not get the feeling he has learned his lesson.

Beatrix Potter bought Hill Top in the throes of mourning her fiancé, publisher Norman Warne, who had believed in her as much as he had loved her. She poured her grief into the cottage and its garden, especially the vegetable patch. She would eventually marry a solicitor, move to the other side of the village and even purchase several farms, but she never relinquished her first outdoor space, somewhere she could call her own, somewhere she could became a benign Mrs McGregor.

Literary Gardens by Sandra Lawrence

Extracted from Literary Gardens by Sandra Lawrence illustrated by Lucille Clerc, published by Quarto, RRP: $45.00.

Buy Now